[EXPLAINER]

When 22-year-old university student Park Min-ho left his hometown of Yecheon County, North Gyeongsang, on July 17, he told his family he was flying to Cambodia for a job fair.

But about a week later, Park’s family received an ominous call from his number.

The caller, later identified as an ethnic Korean with Chinese nationality, said Park had “caused trouble” and was being held captive. The man demanded 50 million won ($35,000) for his release.

Park’s parents immediately contacted the Cambodian Embassy in Seoul and the Korean police, but authorities were unable to locate him before the caller cut off communication.

Park was eventually found dead on Aug. 8 in a pickup truck near Bokor Mountain in southern Cambodia, his body bearing multiple signs of torture.

His abduction and death triggered a national reckoning over a web of scam networks in the Southeast Asian country that have quietly ensnared hundreds of Korean citizens.

As Park’s family pleaded for help repatriating his remains, Korean media and human rights groups amplified reports of other Koreans who had vanished or become suddenly unreachable after traveling to Cambodia.

Facing a surge of public anger over its initial response, Seoul issued a “code black” travel advisory on Oct. 16 for the Cambodian border towns of Poipet and Bavet, as well as parts of the southern Kampot Province. It also pressed Phnom Penh to cooperate in investigations.

Within a week, Cambodian police said they had arrested dozens, freed several detainees, and deported roughly 60 Koreans to face questioning at home.

How did this crisis come to light?

The discovery of Park’s body near Bokor Mountain in Kampot was the immediate catalyst, but his case is emblematic of a much larger problem.

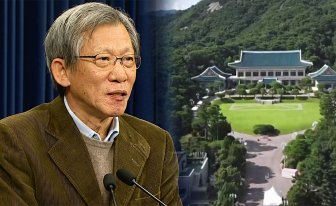

At least 330 Koreans were reported to have been held in Cambodia against their will during the first eight months of this year alone, according to National Security Adviser Wi Sung-lac at an Oct. 15 press briefing, weeks after news of Park’s death spread through Korean media.

As more survivors spoke out, lawmakers and journalists began uncovering compounds across Cambodia that allegedly housed large-scale criminal operations. In these guarded complexes, often surrounded by barbed wire and security guards, victims were reportedly forced to carry out scams under threat of violence.

In one case in early October, two Korean men, who said they had been detained and tortured while being coerced into fraud operations, were rescued after Rep. Park Chan-dae’s office pushed Cambodian police to raid the hotel where they were being held.

By Oct. 16, Korean Vice Foreign Minister Kim Ji-na was in Phnom Penh to demand the Cambodian government’s cooperation in repatriating Koreans and investigating Park’s death.

The Korean public’s reaction — marked by grief, fury and a sense that Seoul had been slow to protect vulnerable citizens — transformed an otherwise criminal justice matter into a full-blown political emergency.

Under mounting pressure, Cambodian authorities deported nearly 60 Koreans found in suspected compounds. Seoul arranged a charter flight, and the deportees arrived at Incheon Airport on Oct. 18 under police escort.

Days later, prosecutors sought arrest warrants for 59 people from the group, saying they had either organized or materially participated in elaborate fraud schemes that preyed on fellow Koreans and foreign nationals alike.

Why are criminal groups operating out of Cambodia?

While online fraud networks have long flourished across Southeast Asia, Cambodia has become a particularly fertile ground for these operations.

Its border towns and coastal provinces offer inexpensive real estate, cheap labor and weak regulatory enforcement — conditions ideal for crime on an industrial scale.

The Covid-19 pandemic deepened that vulnerability. As tourism evaporated, shuttered casinos and hotels were converted into walled-off call centers that actually functioned as so-called crime compounds, where hundreds of workers operated fake investment and romance scams targeting victims across Asia.

A report by Amnesty International this month identified at least 53 such crime compounds in Cambodia, documenting “systematic torture, forced labor and deprivation of liberty.” The report linked the operations to Chinese organized crime syndicates that pivoted to cyber scams after Beijing banned online gambling and tightened border controls during the pandemic.

Amnesty accused Cambodian authorities of complicity, citing cases where police raided compounds, only for them to reopen later. The organization urged the government to close all known sites, prosecute perpetrators and investigate officials who looked the other way.

Officials in Phnom Penh insist they are cracking down, yet progress remains inconsistent. Corruption and dependence on foreign investment, in particular, have blunted enforcement.

Who is behind these criminal schemes?

The operations are sprawling, complex and far from uniform.

Reports describe a layered industry in which criminal syndicates resemble multinational corporations, complete with executives, recruiters and middle managers. The scams they run range from voice phishing and cryptocurrency fraud to elaborate romance ploys that manipulate victims into transferring money.

Authorities say many of the Cambodia-based syndicates are run by Chinese nationals or mixed teams of Chinese and ethnic Koreans from China. They handle everything from recruiting to logistics and IT operations.

In Park’s case, Cambodian prosecutors have indicted three Chinese nationals with involvement in his death.

Local facilitators — including property owners, brokers and, in some cases, officials accused of collusion — have also been linked to the networks’ ability to operate for months or years from fortified compounds.

And crucially for Seoul, some of those involved are Korean.

While some were coerced, others reportedly act as intermediaries — recruiting fellow Koreans, providing translation or setting up local bank accounts under borrowed identities to launder proceeds.

On Sunday, Korean police arrested a suspect accused of persuading Park to open a bank account before arranging his travel to Cambodia.

How are Koreans being recruited or lured into these schemes?

Many Korean victims trace their ordeal to enticing job postings online — offers promising high salaries for seemingly legitimate tasks like translation or data entry.

After initial contact, communication typically moved to KakaoTalk, the ubiquitous Korean messaging app, where recruiters cultivated trust, arranged travel, and often paid for airfare and visas. The illusion of legitimacy crumbled upon arrival, when new recruits found themselves confined in guarded compounds and ordered to work long hours on fraudulent schemes.

But some recruiters have admitted to Korean reporters that many recruits are aware that the operations skirted the law.

Jeon Dae-sik, vice president of the Asian Federation of Korean Business in Cambodia, told the JoongAng Ilbo in an interview earlier this month that more and more Koreans are entering Cambodia fully aware that they are joining operations involving voice phishing and romance scams.

But for unwitting victims, initial work arrangements appear to collapse into coercion, with passports and phones being confiscated, threats issued to relatives and physical punishment meted out to enforce quotas. Several survivors described being beaten or electrocuted for failing to meet targets.

In other cases, coercion began outside the compounds. On Sept. 21, a Korean national in their fifties was kidnapped and tortured by four Chinese nationals and one Cambodian after leaving a cafe in Phnom Penh. Another Korean, a forty-year-old office worker, disappeared during a six-day trip to the capital and was later found in a coma.

The pattern — a plausible job offer, facilitated travel, isolation and forced criminal labor — has repeated often enough that authorities now emphasize predeparture warnings, the removal of illegal job postings and public education.

How are the Korean and Cambodian governments responding?

The two governments have moved largely in parallel — but not without tension — as the scandal has widened.

Seoul has imposed travel restrictions for several Cambodian regions, established an emergency interagency task force, and pledged full investigations into returnees.

The Korean Ministry of Employment and Labor has tightened oversight of overseas job listings. All advertisements involving Cambodia now require pre-approval, and keyword filters are being developed to detect possible scams during registration.

South Korea has also proposed creating a “Korean Desk” — a permanent liaison unit within the Cambodian National Police — to coordinate future cases. A similar initiative in the Philippines has helped deter crimes targeting Korean residents by improving information sharing and expanding local CCTV networks.

Phnom Penh, meanwhile, has conducted raids, arrested foreign suspects and repatriated those found in scam compounds. But progress has been uneven, and Seoul has pressed for greater transparency in prosecutions.

“Cambodia’s police capabilities are limited,” a Korean Foreign Ministry official told the JoongAng Ilbo earlier this month. “Trying to impose Korean-style solutions will not produce results. We must work with the National Police Agency and other ministries to urge a constructive stance from Cambodian authorities.”

The cooperation has been complicated by reports that Cambodia demanded the extradition of political dissidents living in South Korea in exchange for handing over suspects involved in crimes against Korean nationals — a claim that neither side has publicly confirmed.

“Police cooperation with Cambodia is less effective than with other Southeast Asian countries,” said Yoo Jae-seong, acting commissioner general of South Korea’s National Police Agency, during an Oct. 13 briefing.

Meanwhile, lawmakers in Seoul have demanded accountability — not only from diplomats and police, but also from social media companies and job platforms accused of failing to block fraudulent postings.

But for Park Min-ho’s family, those questions come too late.

Seventy-four days after he left home, his ashes were returned to Yecheon. His death, as well as similar cases now under scrutiny, have become a test of how far Korea can go to protect its citizens abroad — and how long Cambodia can avoid confronting the criminal networks thriving within its borders.