Chung Hyo-shik

The author is the social news editor at the JoongAng Ilbo.

The Seoul Southern District Court’s acquittal of Kim Beom-su, founder of Kakao and head of its Future Initiative Center, in his first trial on charges of manipulating SM Entertainment’s stock price drew attention less for the verdict itself than for the presiding judge’s remarks. Chief Judge Yang Hwan-seung criticized investigators’ use of “separate, unrelated cases” to pressure suspects into confessions, warning that such practices “distort the truth and lead to unjust results.” His comments carried particular weight as Korea prepares to divide investigative and prosecutorial powers next October — eliminating the prosecution service and transferring investigations to the police and a new Serious Crimes Investigation Agency, while a separate Office of Public Prosecution will handle indictments.

The 124-page ruling also detailed how a separate investigation into Lee Joon-ho, former head of investment strategy at Kakao Entertainment, influenced the case. The probe began when HYBE, which had failed to acquire SM Entertainment after a public tender offer in February 2023, filed a complaint with the Financial Supervisory Service (FSS). In November of that year, the prosecution, after receiving the case from the FSS’s special judicial police, unexpectedly raided Baram Pictures, a company previously owned by Lee.

Before Kakao Entertainment acquired Baram Pictures for 40 billion won ($28 million) in 2020, Lee and his wife, actress Yoon Jung-hee, had been the majority shareholders. Both were booked on charges of breach of trust. Lee was subjected to two arrest warrant requests and growing pressure as his wife became entangled in the case. After six interrogations by the FSS and prosecutors in which he denied wrongdoing, Lee changed his statement after the Baram raid, saying he had conspired to manipulate SM Entertainment’s stock price. He later applied for leniency under a new “self-reporting” clause in the Capital Markets Act and was exempted from indictment.

The court, however, dismissed his confession as unreliable. “Lee had a clear motive to cooperate with investigators to avoid being charged,” the ruling stated, rejecting his testimony as untrustworthy.

Lee was separately indicted over the Baram Pictures deal but was acquitted by the same court in September. The judge ruled that Baram was “a valuable company, having signed contracts with renowned screenwriter Kim Eun-hee and Studio Dragon for major drama projects,” adding that “even if its valuation and acquisition price differed significantly, it cannot be concluded that Kakao Entertainment suffered losses.”

The controversy over byeolgeon susa — the use of separate or unrelated cases to pressure suspects — is not new. Prosecutors have long defended such tactics as necessary to uncover hidden crimes. The 2003 illegal presidential campaign fund probe, one of the prosecution’s most famous successes, relied on separate bribery investigations into business executives. But later cases left deep scars. The 2009 probe into former President Roh Moo-hyun, triggered by a tax evasion case involving Taekwang Industrial Chairman Park Yeon-cha, was denounced as political retribution and fueled the movement to abolish the prosecution, which is now scheduled to occur in 2026.

President Lee Jae Myung, whose own indictments evolved from the Daejang-dong development scandal into multiple related cases — illegal corporate donations to Seongnam FC, alleged payments to North Korea and the misuse of corporate credit cards — has often said he is “the greatest victim of prosecutorial overreach.”

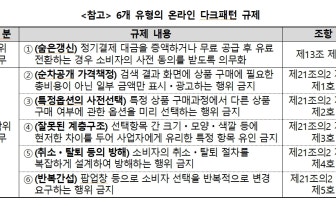

Yet the question remains: Will eliminating prosecutors end coercive investigations? The boundary between “separate” and “additional” investigations is not always clear. During the Moon Jae-in administration, lawmakers sought to ban separate probes outright through an amendment to the Criminal Procedure Act that would have limited prosecutors to investigating within the same factual scope as transferred police cases. That clause was later softened to allow cases “within the bounds of factual similarity.”

As Judge Yang noted, the challenge now is whether the police and the new Serious Crimes Investigation Agency can uphold human rights and the presumption of innocence, avoiding the performance-driven culture of arrests and convictions that long defined the prosecution. The same question applies to special prosecutors who have faced criticism for excessive or politically motivated investigations.

In that sense, banning separate investigations may prove far more difficult than simply dividing the powers of investigation and prosecution. Kim Beom-su’s acquittal has reopened an uncomfortable but necessary debate about how far the justice system can go in pursuing the truth without crossing the line into coercion.

This article was originally written in Korean and translated by a bilingual reporter with the help of generative AI tools. It was then edited by a native English-speaking editor. All AI-assisted translations are reviewed and refined by our newsroom.