A growing gender gap in Korea’s National Pension scheme is contributing to a high poverty rate among elderly women, according to a new study on Monday.

Kim Tae-il, a professor of public administration at Korea University, revealed the disparity at a symposium on pension reform and fiscal sustainability hosted by the Institute for Future Policy Studies at Sungkyunkwan University on Monday.

Men aged 55 to 59 — the final age group eligible for mandatory pension contributions — had paid into the pension for an average of 18.8 years as of 2019, more than twice the 8.9 years for women in the same age group, according to Kim’s analysis.

The gap widens further when broken down by income brackets. Among those in the 5th quintile, the top 20 percent, of male earners, the average contribution period was 24.6 years, compared to just 6.1 years for women in the lowest income group.

Of pension subscribers in the 55 to 59 age group, 92.8 percent of men had met the minimum 10-year contribution period required to receive old-age benefits. Only 22.7 percent of women had done so, leading many to voluntarily continue paying into the system past the age of 60 to qualify for a pension.

As of June this year, there were 322,629 women enrolled as voluntary contributors — 2.27 times more than the 142,182 men in the same category. Under current law, 59 is the upper limit for mandatory participation in the pension program.

However, individuals may choose to continue making contributions after that age. Voluntary contributors must pay the full 9 percent of their income themselves, unlike those under 60, whose employers cover half.

Kim also found that women in their 30s and 40s are significantly underrepresented in the pension system. Among people aged 35 to 39, 82.7 percent of men were enrolled in the pension scheme, compared to just 57.6 percent of women. In the 40 to 44 age group, the rates were 81 percent for men and 59.3 percent for women.

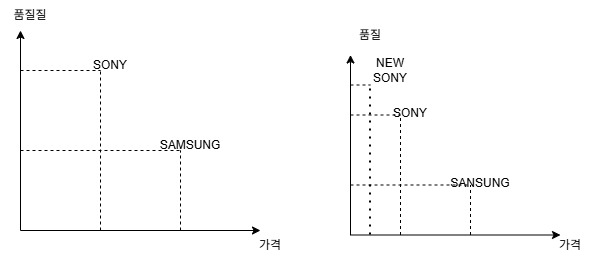

Because of their lower participation and shorter contribution periods, women receive considerably smaller pension payouts. The pension amount is primarily determined by how long a person has contributed — more so than by how much.

Those with over 20 years of contributions are eligible for what is called a “full old-age pension.” As of June, 1.05 million men were receiving this benefit, compared to only 210,000 women — a fivefold gap.

By contrast, the number of partial pension recipients — those who contributed for between 10 and 19 years — was higher among women: 1.4 million compared to 1.32 million men.

The disparity is even starker when looking at monthly payouts. There were 79,118 men receiving over 2 million won ($1,400) per month, compared to just 1,647 women. The largest concentration of male pensioners was in the 600,000 to 800,000 won range, while the majority of female pensioners received between 200,000 and 400,000 won.

A similar income-based gap was also observed in Kim’s analysis. Among subscribers aged 30 to 59, 59 percent in the lowest income quintile were enrolled, compared to 74.2 percent in the top quintile. In the 55 to 59 age group, the lowest quintile had an average contribution period of 10.2 years, while the top quintile had 19.5 years.

Only 35.7 percent of low-income subscribers met the minimum 10-year requirement, compared to 76.1 percent in the top income group.

The inadequacy of women’s pensions is a key factor in elderly poverty. The poverty rate for elderly women in 2022 was 43.4 percent, 12.2 percentage points higher than the 31.2 percent rate for elderly men, according to the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs.

“It’s hard to find another country where income- and gender-based disparities in pensions are as extreme as in Korea,” Kim said. “Is this really a pension for the people?”

“A contribution period of less than 20 years is not in line with the purpose of the pension system,” added Kim. “We need to set goals to expand the contribution period and eliminate blind spots, and focus on these issues.”

This article was originally written in Korean and translated by a bilingual reporter with the help of generative AI tools. It was then edited by a native English-speaking editor. All AI-assisted translations are reviewed and refined by our newsroom.

![Elderly women are seen at a temple in Gangbuk District, northern Seoul on Oct. 14. [NEWS1]](https://imgnews.pstatic.net/image/640/2025/10/21/0000078561_002_20251021120610983.jpg?type=w860)

.jpg?type=nf190_130)

.jpg?type=nf190_130)