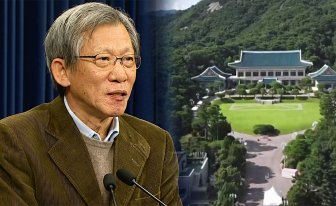

Cho Won-Kyeong

The author is a professor at UNIST and the head of the Global Industry-University Cooperation Center.

The new administration has announced its third housing policy, expanding regulated zones. Regulatory efforts are also spreading abroad. In New York, tenants spend about 29 percent of their pretax household income on housing. After adjusting for disposable income, the burden is even heavier, prompting Democratic mayoral nominee Zohran Mamdani to campaign on a policy of freezing rent levels. In California, where median home prices are more than double the national average, even middle-income families can hardly buy a house. In Los Angeles, median rent equals 34 percent of the median income. Against this backdrop, state governments have introduced rent caps and tenant protections, though such measures risk reducing supply and distorting markets over time.

Romania, where socialist-era policies fostered the “one household, one home” norm, now has the highest homeownership rate in Europe. Yet the outcome has been a concentration of property wealth, inflexible transactions and a weak rental market — proof that high ownership does not guarantee housing stability.

Korea faces a similar dilemma. The government aims to curb speculation by expanding the land transaction permit system, which requires government approval for property purchases in designated areas. But such controls, despite good intentions, often bring unintended results. They slow property sales, reducing jeonse — Korea’s lump-sum deposit lease system in which tenants pay a large upfront sum instead of monthly rent — and push landlords to switch to monthly contracts. This shift strains household cash flow and raises housing costs for tenants. Meanwhile, supply contraction and heightened expectations can paradoxically drive prices upward.

Rent controls ease housing costs in the short term but are no structural solution. Without parallel efforts to expand supply and raise income, renters in both New York and Seoul will remain trapped in insecurity. Overreliance on regulation may erode public trust and deepen social frustration.

The real answer lies not in tightening the market but in creating space for people to breathe — policies that expand opportunity rather than restrict it.

This article was originally written in Korean and translated by a bilingual reporter with the help of generative AI tools. It was then edited by a native English-speaking editor. All AI-assisted translations are reviewed and refined by our newsroom.