In June of 2014, homophobic forces blocked the queer pride parade from marching in Shinchon, Seoul by holding a rally masquerading as a “memorial ceremony for the sinking of MV Sewol”. Essentially, their argument was “How can such a perverted festival take place when the entire country is in mourning?” Lying on the ground for f0ur hours to block the parade, these individuals shouted, “Homosexuality is a sin!” A few months later, they stood in front of the bereaved families of the Sewol ferry tragedy. Once again, they shouted. “Don’t force citizens to mourn!” “Don’t divide public opinion!”

‘Hate’ is now one of the keywords that describe Korean society. It is no longer an issue confined to minorities such as sexual minorities or immigrants. Even an ‘ordinary’ person who seeks to live as who they are, or who discloses a difference of opinion, can become the target of hate. What is hate, and how can we live in an era in which hate has become mundane? A film that poses these heavy and painful questions has been released: the documentary Troublers.

Director Lee Young has been amplifying the voices of those made invisible by society through films such as Turtle Sisters (2002), about disabled women’s independence, and Lesbian Censorship in School (2005) and Out: Smashing Homophobia Project (2007), both of which dealt with the stories of teenage sexual minorities. In Troublers, Lee intercuts scenes of hate speech groups in Korea, the story of Lee Muk, who is a bajissi[1] in their 70s, and the story of a Japanese lesbian couple, Non and Ten, whose lives have changed since the 3.11 Great East Japan earthquake.[Also known as the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake]

[1] Bajissi is a compound of the Korean word for “trousers”, baji, and the honorific used among people of approximately equal status, ssi. The corresponding feminine term is chimassi, a compound of chima (skirt) and ssi. In a Q&A session following a Troublers screening, Director Lee Young responded to an audience question on the origin of the term in the following way:

“Bajissi, chimassi are slang terms used in lesbian communities in the 60s and 70s, and refer to certain styles of dress. A masculine person was referred to as bajissi, and a feminine person as chimassi. I also heard the term bajissi being used in the late 90s, when I was in my late 20s. I think you can think of it as a word used [by sexual minorities] in a period when words like ‘lesbian’ and ‘transgender’ were not used.”

In the essay “A 10 Year History of the Korean Lesbian Rights Movement” included in anthology The History of Korean Women’s Rights Movement (1999), Lee Hae Sol writes that the terms bajissi and chimassi are thought to have been coined by the Women Taxi Drivers’ Association (여자택시운전사회), which could be said to be the first community of women sexual minorities.

-References: http://www.arthousemomo.co.kr/pages/board.php?bo_table=cinetalk&wr_id=1791, http://lgbtpride.tistory.com/1301, http://jbreview.jinbo.net/maynews/article_print.php?table=organ&no=443 (Korean text)

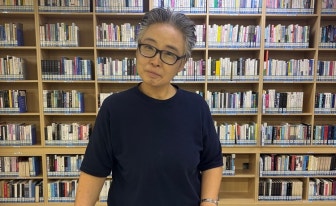

In anticipation of the film’s screening at the 41st Seoul Independent Film Festival, we met Ms. Lee at the office of Feminist Video Activism WOM.

- Troublers had its premiere last September 2015 at the 7th DMZ International Documentary Film Festival. The screening was sold out and the film received the Special Jury Award in the Korean Competition section. How was it received by the audience? Were there any audience reviews that made a strong impression on you?

I saw a review written by a blogger that said, “‘Troubler’ has become a label that is an effective tool in instigating the masses. Communists are an object of hatred, and that hatred is very easily transferred to other groups. When the objects (of hatred) are minorities or disadvantaged people, the spreading becomes even easier.”

I read this review and felt happy because the film’s intention seemed to be well understood. In addition, an audience member who is a sexual minority posted the following on their homepage after seeing the movie:

“The moment the utterances ‘Don’t force citizens to mourn’, ‘Don’t wallow in sadness, live quietly’ (said to the Sewol tragedy’s bereaved families) overlap with the utterance ‘Don’t come out in public spaces’ directed at sexual minorities, the film creates a scene in which the Sewol ferry sinking becomes an important issue that we must deal with seriously in queer politics.”

I thought it was meaningful that a sexual minority audience member felt this way. “I’m happy that there are diverse interpretations of the film.”

- The direct aggression, instigation, and crazed behaviors of the hate groups comprise a large portion of the film. The audience experiences hatred vividly, and perhaps because of this I heard that many felt pain and cried watching the film.

Hate as a phenomenon is being widely discussed in Korea, but in film, there hasn’t been a portrayal of what it is specifically. Hate is not simply disliking something. Instigating hate in public spaces, carrying out physical attacks, creating fear, producing blind hostility—all of this is hate. I thought I needed to show how hate surfaces in specific incidents.

I felt pained while making the film, so of course I empathize with the audience members, especially the sexual minority audience, who feel that way. But I think this is an aspect of Korean society that we need to face.

When I first met the hate groups during the three years I was making this movie, I was very angry. They were instigating the public with lies, disseminating misleading information, and holding campaigns that expanded social prejudices. But I also felt dejected. These weren’t special people, but people you could find anywhere. They were of my parents’ generation, people who look like the woman or man next door, or youth I might meet in my neighborhood.

-There are scenes in the film where you are roughly restrained while filming the hate groups. Did you feel your personal safety was threatened as you were filming?

Throughout the shooting, we were repeatedly asked to “identify” ourselves. We look different in appearance, so they knew we were different from them and kept asking who we were and what organization we were from. I said that Imake documentaries, gave them my name, and told them what my purpose was in making the film. Even then, though, I kept being asked to “reveal my identity”. There were other reporters at the scene, but only our camera would get blocked, or they would obstruct us by covering or shoving away our camera.

I won’t be surprised if I get sued (for defamation). The hate group members kept saying that they would take legal measures, because they thought the film would distort what they are saying or portray them in a bad light. They could also rally against screenings of the film or put in complaints at the screening locations so that the screenings get cancelled. I am concerned about these possibilities.

-Who does the film’s title, Troublers, refer to? Does it also include the director?

At first I started with lesbian and gay people. They are being talked about as “troublers” who destroy families and ruin the country. In South Korea, it’s come to the point where the words jongbuk (pro-North Korea) and gay have been combined into one phrase, jongbuk gay (pro-North Korea gay), and people say that “homosexuals are the left’s ultimate weapon”, even though in North Korea, homosexuals are being executed.

However, now the “troubler” label or stigma is being attached to anyone who is even slightly critical about society. I am included in the term “troublers”, and it also refers to the growing group of people who are being called this name. The audience members who’ve seen the film now pose questions to those who have labeled others “troublers”: Who exactly are the people that you, the hate groups, call troublers? Aren’t you the ones who are troublers?

Lately, people who voice criticism about the national standardization of history textbooks are called troublers. When I watched the news, I noticed that the people shouting, “People who are against national textbooks are not citizens of Korea” were the same people who caused a scene at the forum on the revision of the Student Rights Ordinance by yelling that “students are not singing the national anthem”, and the ones who disparaged the bereaved Sewol families by calling them “nation-dividing forces”.

- I was very interested in the scenes with Lee Muk, the bajissi. What role does Lee Muk play in the film?

Lee Muk is not someone who is currently a direct target of hate attacks. But Lee is someone who lived their whole life, for 70 years, constantly being questioned about their place in society. I think the hate attacks we see now are a result of sexual minorities having some visibility, but Lee Muk lived through times when sexual minorities were not even named as such.

Trousers are considered men’s clothing. I wanted to talk about how an individual’s life, Lee Muk’s life and identity, were influenced by living in a time when women weren’t able to be economically and socially active, in a period of such prejudice and stigma. In addition, I wanted to illuminate the strength that Lee Muk had that enabled them to endure (without letting go of their identity) for 70 years.”

-Is bajissi a term that we could say corresponds to “butch lesbian” today?

It has been explained as an analogue to “butch lesbian”, but it cannot be described only as that. Their lives existed beforehand, and I think it may not be fitting to use language that came afterward to define those lives. Bajissi could be transgender, intersex, or genderqueer (a gender identity that goes beyond the binary of man or woman), too. I hope that they will be more deeply understood.

-In the film, there is a scene where Lee Muk carefully washes and hangs their chest covering. It read to me as an effort to protect their identity.

The chest covering is called malgi (roller) and is nowadays more often called a “binder”. Lee Muk wears momppe pants when they are in the countryside (their place of origin) and doesn’t wear the malgi there. When they are in a space where people know who they are and understand them, they don’t wear the malgi. But when they are in the city, Lee says, “This town likes it when I eat[ i.e. “when I spend money”], but otherwise I need to be tactful.” Here Lee Muk wears the malgi and lives with a different name.

Depending on the location and the relationship, Lee Muk has lived by concealing or revealing a part of themself to uphold who they are. I think that revealing themself was a process of struggle. It would have always been a challenge. Malgi is a symbolic expression of this life of 70 years.

- You also tell the story of a Japanese lesbian couple, Non and Ten. After the Great East Japan Earthquake, they decided to come out publicly and had a wedding. How did you meet them?

In 2012 and 2013, there were rumors that there was going to be a war in Korea. ‘Where would we seek refuge?’ My friends and I discussed, ‘Can we even live in a refuge center? How would our lives be there?’ And I started to wonder. How are sexual minorities living in areas that experienced the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011? As they are socially disadvantaged even in ordinary life, I wondered how they were living in the extreme situation of natural disaster, which makes them even more vulnerable. So I immediately went to find them.

When I went there and heard their stories, I learned that transgender people, who need hormone treatment and so require certain medications or other medical support, were unable to receive such medical aid in natural disasters. Sexual minority couples’ lifestyles were not protected in the refuge centers either. I heard that this led them to remain in their collapsed houses at the devastated sites instead of going to the refuge centers. My heart ached for them, and I felt sad. I could empathize with them. That’s how Non and Ten’s story began.

- We can’t skip over the topic of Feminist Video Activism WOM. I heard the members have breakfast together every day. Is that still true?

Yes, we still eat breakfast together. We gather in the morning and eat, have a quick briefing, have tea, and go out to work. We head back in the evening, eat and work, and talk over drinks. We make a living together and share our resources with each other. It’s an economic community. And a community for daily life.

When we began WOM in June 2001, we only had passion and determination. We began with the question of how we could lead a sustainable life working in film, so we thought, “We will share all resources,” and, “We’ll earn together and spend together.” How we as lesbians can live a more feminist life, how we can sustain ourselves as a feminist community, and how we can live in a different way… There have been ups and downs, and we’ve been experimenting and challenging ourselves for over 15 years.

-How many members are in WOM?

There are four people. Director Lee Hye Ran (maker of the 2006 documentary We Are Not Defeated, which explored the struggle of women laborers at the Dong-il Textile Company) and I are the full-time members, and the other two join when there is something to do together. Lee Hye Ran is also a producer, and she played a key role throughout the entire production of Troublers, including helping with filming and editing.

- Perhaps because feminists are strong personalities and not the most friendly people, I’ve never seen a feminist community last for such a long time in a tight-knit relationship. (Laughter) Is there a secret to how WOM has been able to keep going?

It’s probably because of desperate need. “I want to make feminist documentaries, and I want to live.” It’s hard to make documentaries, and it’s hard to live as feminists. We knew it’d be hard to meet other people or find chances to live this kind of life or do this work together.

There were painful moments that were hard to endure. Even if we may not have yelled, “It hurts”, there were moments of definite anger, but I think we were able to let it simmer down and come back together because of the desperate need. Whether you are an individual director or working as a group, it’s hard to live as a documentary director. Who else would we engage in this new experiment and challenge of ‘feminist documentary’ with?

I think that Lee Hye Ran has been very considerate with me, and that has helped me continue my life. We are colleagues in feminism, but she has greater experience in film production, so I respect her. It’s not that there is a hierarchy, but it’s not horizontal equality either. We have very different sensibilities, so we cannot make something new without respect for each other. If you don’t have mutual respect, you simply end up with a comprise or the ‘average’ of two opinions, but art shouldn’t be standardized.

- For the past 3 years, you have observed at close hand the growth of hate groups in Korea. You must also have thought deeply about what we should do.

These days it is true that every day something shocking or difficult to understand occurs and makes us feel as though we are going 20, 30 years back in time. But especially in times like this, I think it’s important to do what we can where we are, and voice our opinions. It’s not about having or not having hope. Raising our voices to live just as we are in this society now—isn’t that what’s needed? If you think about how you cannot see ahead, or that the future feels dark, or that you cannot do anything, then you really can’t do anything. I think we need to do something now, where we are.

-Do you want to say anything to the future viewers of Troublers?

People cannot help inhaling a social atmosphere of hate, and hate has become the environment surrounding us. I hope the film inspires you to think about what it means to coexist in this age, and how we can coexist with other people.

*Original article: http://ildaro.com/7296 Published: November 24, 2015. Translated by Hoyoung Moon

◆ To see more English-language articles from Ilda, visit our English blog(https://ildaro.blogspot.com).